3 decision-making lessons from ‘A Christmas Carol’

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens is a classic tale that reminds us of the true spirit of Christmas. It also provides powerful lessons on decision-making which, like the book itself, have stood the test of time.

As we know, the tale describes the transformation of Scrooge one Christmas Eve from “a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner,” to someone overflowing with joy and generosity by Christmas morning, eager to make amends for his selfish behavior.

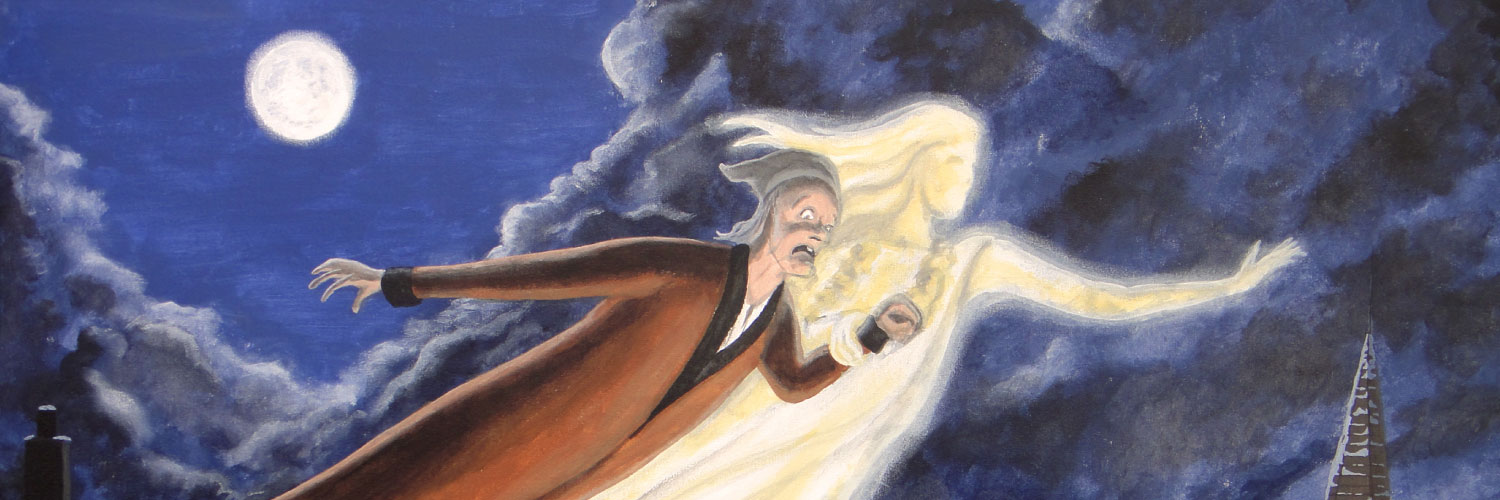

The catalyst for his epiphany is the frightening appearance of a spirit wrapped in chains – Scrooge’s long dead partner Marley – warning him that he will be visited by 3 ghosts. As they visit Scrooge, each guides him on a magical journey through his Christmases of the past, the present, and a potentially bleak future. Scrooge slowly realizes that he’s made some poor decisions throughout his life and finally understands that it’s not too late to make some better ones.

The lessons behind Scrooge's transformation

1. Widen your decision frame

A decision frame is the set of assumptions, beliefs, values, and perspectives through which we view a particular decision or group of decisions. The frame we choose tends to drive the options we see. The narrower the frame, the fewer options we see.

From the early pages of the book, it is clear that Scrooge views every decision through a singular narrow frame – optimizing personal wealth and gain. On Christmas Eve, Scrooge’s nephew cheerfully invites him to a festive dinner with friends and family. Scrooge not only declines, but he also ruthlessly mocks his nephew. “What’s Christmas time to you but a time for paying bills without money; a time for finding yourself a year older, but not an hour richer.”

Scrooge works in a trading house in London with his younger, and much less paid clerk, Bob Cratchit. It is a cold Christmas Eve and Scrooge is reluctant to spend money on coal to heat the office. “Scrooge had a very small fire, but the clerk’s fire was so very much smaller that it looked like one coal.” When Cratchit attempts to shovel more coal on his fire, Scrooge threatens to fire him: “Wherefore the clerk put on his white comforter and tried to warm himself at the candle; in which effort, not being a man of a strong imagination, he failed.” Not only is Cratchit uncomfortable, but we also soon find out there is true suffering in his family, suffering Scrooge is oblivious to given his narrow decision frame.

He’s most concerned about piling up his wealth, which blinds him to other possibilities. However, with the help of the ghost of Marley and the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future, Scrooge begins to widen his decision frame, and as he does so he begins to consider other options and the value inherent in each.

2. Avoid the self-interest trap

Every human has some level of self-interest; it is what allows us to survive. To pretend that self-interest doesn’t underlie many of our decisions would be disingenuous. The problem is that when self-interest is unacknowledged, it can lead to sub-optimal decisions.

Later on that Christmas Eve, two gentleman, appealing to the season of giving, solicit Scrooge for a donation to the poor, asking him, “What shall I put you down for?”

Scrooge’s answer: “Nothing!”

When Scrooge claims he already gives to the poor houses, prisons, and asylums prevalent in the London of his day, the solicitors reply: “Many can’t go there; and many would rather die.”

“If they would rather die,” says Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Scrooge has almost no concern for the wellbeing of others in his community, especially the less fortunate. He is focused exclusively on himself, and because he believes that money is what brings happiness, he goes about his days doing everything he can to maximize his wealth, to the detriment of almost everything around him.

Although Scrooge is an extreme example, the self-interest trap is an ever-present obstacle to good decision-making. The best way to counter it is to explore how our own self-interest may blind us to the interests of others in a decision and lead to a sub-optimal decision. One way to do that exploration is to take on the perspective of an objective observer, and ask ourselves how that objective observer would view the situation.

For Scrooge, the objective observer “role” is played by the spirit of his deceased partner, Jacob Marley, and the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future, and it is Marley’s ghost who first warns Scrooge that the self-interest decision-making trap is not a path to happiness. Scrooge is surprised to learn that Marley has been sentenced to ceaselessly wander the earth as penance for his extreme selfishness while alive. Scrooge had always believed Marley was a successful person, saying, “But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,”

“Business!” cried the ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

Here Marley is encouraging Scrooge to both break out of his self-interest decision-making trap and also widen his decision frame to include the interests of the “common welfare” and “mankind.”

3. Talk over your decision with an honest friend

While Scrooge’s change of heart is partly due to the scenes he experiences, equally important is the way the ghosts drive certain points home. For example, when the ghost of Christmas Past reveals a scene from Scrooge’s childhood showing a younger version of Scrooge interacting happily with his sister, the ghost says:

“She died a woman, and had, as I think, children.”

“One child,” Scrooge returned.

“True,” said the Ghost. “Your nephew!”

Scrooge seemed uneasy in his mind; and answered briefly, “Yes.”It is evident Scrooge is recalling that earlier scene when he rejected his nephew’s invitation for dinner on Christmas Eve and made fun of his joyful embrace of Christmas.

Later, the ghost of Christmas Past reveals a moving scene from Scrooge’s time as an apprentice to Mr. Fezziwig, a jolly fellow full of warmth and good cheer. The scene is from a Christmas Eve many years earlier and Mr. Fezziwig is hosting a party packed with people in high spirits and couples dancing to a fiddle. Scrooge is moved by what he sees, recalling how happy his earlier self was to participate in the Christmas celebration.

However, the ghost helps Scrooge connect the lesson of Mr. Fezziwig to his present life when he sarcastically reminds Scrooge that what Mr. Fezziwig is doing is a “small matter” because Mr. Fezziwig spent only a few pounds on the party, which, given Scrooge’s narrow frame of valuing everything in pounds, means it must have had only a small impact.

“It isn’t that,” said Scrooge, heated by the remark, and speaking unconsciously like his former self. “It isn’t that, Spirit. [Mr. Fezziwig] has the power to render us happy or unhappy; to make our service light or burdensome; a pleasure or a toil. Say that his power lies in words and looks; in things so slight and insignificant that it is impossible to add and count ’em up: what then? The happiness he gives, is quite as great as if it cost a fortune.”

It is because of these conversations with the ghosts that Scrooge begins to see things from a new perspective, and as a result, regret many of his past decisions.

What we can learn from Scrooge

In short, Dickens uses Scrooge and The Christmas Carol to remind us of 3 of the powerful decision-making skills that we teach in Decision Mojo:

- Widen your frame to consider more options.

- Consider how your decisions impact others.

- Have a dialogue with a friend, colleague or conversation partner who can be objective. (See our recent post on “8 ways to use generative AI to improve decision-making”)

More decision-making lessons

There are also some other lessons in A Christmas Carol that we also teach:

- Tap into your past experiences and knowledge.

- Mentally project yourself into the future and consider how your decisions will impact your future self (aka the 10-10-10 technique that we teach)

- Take time for reflection: “Sleep on it.”

Perhaps the most enduring power of A Christmas Carol is the idea that there is a little Scrooge in all of us. By reading the story every year or so, we remind ourselves of its timeless lesson: It's never too late to get a little bit better at making the big and little decisions that make us who we are.

- 3 decision-making lessons from ‘A Christmas Carol’ - December 19, 2023

- 8 ways to use generative AI to improve decision-making - December 4, 2023

- The NBA’s 3-point shot provides a cautionary tale for leaders navigating disruptive innovation - May 30, 2023